Paul Cardin, [11/10/2025 17:27]

“Will / do UK centres house quantum computers?”

Yes, UK centres do house quantum computers. The National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC), located at the Harwell Campus in Oxfordshire, is a 4,000 square meter facility that will house 12 quantum computing platforms, offering open access to industry, academia, and other sectors across the UK.

The centre was officially opened in October 2024 and is designed to support world-class research in quantum computing hardware, software, and applications development.

It is part of a broader UK quantum ecosystem that includes regional centres of excellence and five Quantum Hubs hosted at universities across the country, such as the University of Glasgow, University College London, the University of Cambridge, the University of Birmingham, and Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh.

These hubs and the NQCC are supported by a £93 million investment from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and are central to the UK’s ten-year quantum programme aimed at building a scalable quantum computer and fostering innovation across key economic sectors.

Paul Cardin, [11/10/2025 17:28]

“Do these Quantum computers require extremely low temperatures to operate?”

Yes, most quantum computers in the UK and globally require extremely low temperatures to operate, typically near absolute zero.

This is especially true for superconducting qubits, the technology used by leading companies like IBM and Google, and supported by centres such as the UK’s National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC). These systems operate at around 10–50 millikelvin—colder than outer space—using dilution refrigerators to minimize thermal noise and maintain quantum coherence.

However, not all quantum computing approaches require such extreme cooling:

Trapped ion and neutral atom systems operate at slightly higher temperatures but still need cryogenic environments for vacuum and stability.

Silicon spin qubits can function at marginally higher temperatures (a few Kelvin), potentially reducing cooling demands in the future.

The need for ultra-low temperatures is driven by the fragility of quantum states, which are easily disrupted by heat and environmental noise.

Paul Cardin, [11/10/2025 17:31]

“How much electrical power is consumed in order to achieve the extremely low temperatures that are required here? Is there an associated high demand?”

Yes, achieving the extremely low temperatures required for quantum computers involves significant electrical power consumption, primarily due to the dilution refrigerators used to cool superconducting qubits to near absolute zero (around 10–15 millikelvin).

A single dilution refrigerator typically consumes between 25 kW and 50 kW of continuous electrical power. This energy is used not only for cooling but also for operating vacuum pumps, control electronics, and multi-stage refrigeration systems that progressively lower the temperature from room temperature down to the millikelvin range.

This creates a high associated power demand:

The cooling system alone can use as much power as 10 average homes.

While the quantum processor itself uses minimal power (milliwatts), the supporting infrastructure—especially cryogenics and control electronics—dominates energy use.

For example, IBM’s quantum systems require around 10 kW just for control and readout electronics, in addition to the refrigerator’s load.

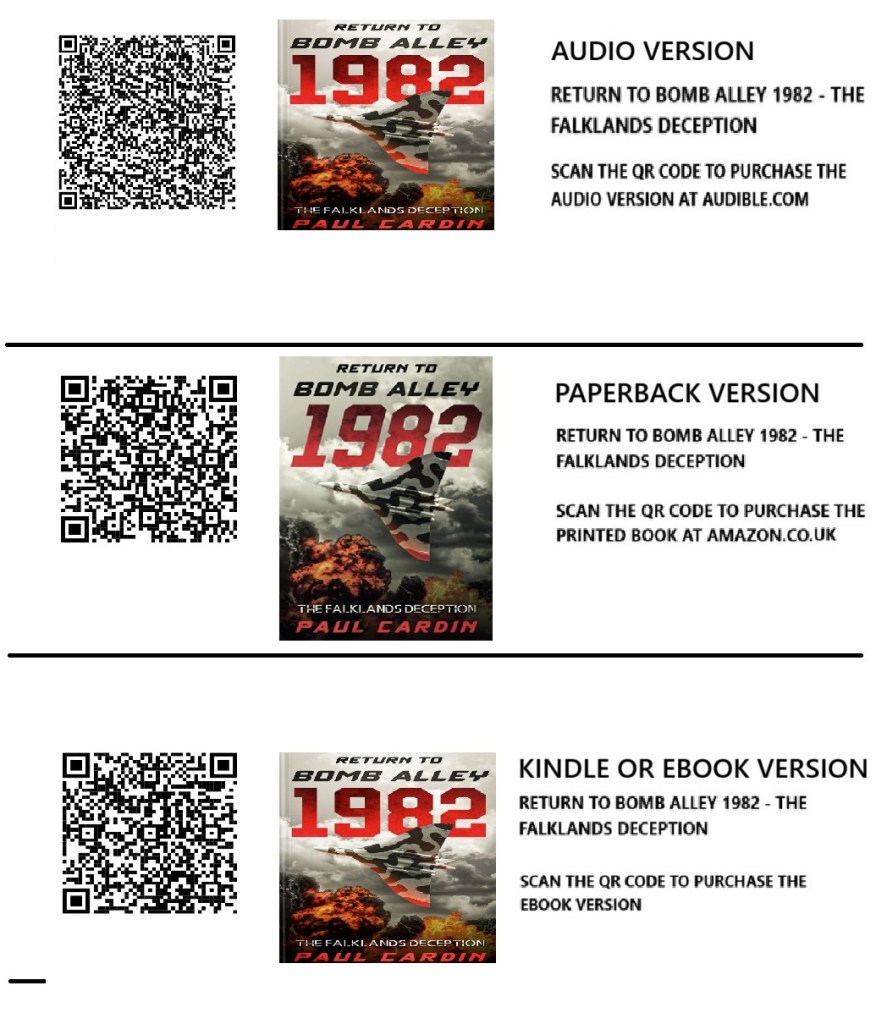

Return to Bomb Alley 1982 – The Falklands Deception, by Paul Cardin

Amazon link